Gucci creative director Alessandro Michele put on a whimsical, eclectic show for his first resort collection in June. Behind the scenes, the company is focused on green production. (Richard Drew/AP)

Gucci is having a renaissance. After years in the doldrums, the 94-year-old fashion house is again the star of glossy magazine spreads, its collections coveted by couture aficionados and celebrities, thanks to the eclectic runway shows masterminded by new creative director Alessandro Michele . Last month, its new boutique opened at CityCenterDC featuring storage units that resemble elegant steamer trunks and expansive tables designed to hold a trove of costly handbags. Lots of handbags. Because at its core, Gucci is an accessories label built on shoes and purses.

And that’s a problem. Not for the company’s bottom line, but for the environment.

Robin Givhan is a staff writer and the Washington Post fashion critic, covering fashion as a business, as a cultural institution and as pure pleasure.

Shoes and handbags mostly depend on leather. And cattle ranching consumes mass quantities of natural resources — from land to water. Traditional leather tanning uses heavy metals, most notably chromium, and the resulting waste is a health hazard. And PVC, another favored component in bag-making, is also an environmental contaminant.

So with little fanfare, this nearly $4 billion business has been making changes. The handbags — namely the trendy $2,400 flower-bedecked Dionysus shoulder bags stitched from the signature GG Supreme canvas print — now use polyurethane in their design rather than PVC.

The Dionysus shoulder bag from Gucci. You wouldn’t know it, but the handbag is actually an example of green — or sustainable — fashion. (Cosimo Sereni/Gucci S.P.A.)

But the marketing doesn’t highlight the switch; only the vaguest reference on the Gucci website notes that it is produced using an “earth-conscious process.”

The new green sensibility of Gucci represents the changing philosophy of its parent company, Kering — one of the largest luxury conglomerates in the world — and the luxury industry in general, including the biggest behemoth of them all, LVMH Moet Hennessy Louis Vuitton. But Gucci’s reluctance to make that shift evident — let alone exciting or sexy for its consumers — highlights the unsettled relationship between the luxury business and eco-fashion.

The quiet changes at Kering and LVMH are laudable, experts say. But with its rapt audience of tastemakers and innovators — and its unique ability to create markets where none existed — luxury could do so much more.

If top-tier brands buffed, glossed and shared the story of how they responsibly manufacture products, they could even make eco-friendly as covetable as a designer logo — and transform the culture’s entire view of manufacturing that is good for the environment.

More than 150 world leaders are meeting in fashionable Paris for the 21st session of the Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. (Martin Bureau/AFP/Getty Images)

Paris — ground zero for luxury fashion — is serving as host to theUnited Nations Conference on Climate Change. Kering executives are sitting on multiple panels, while LVMH, a corporate sponsor of the conference, is firing off email blasts to its employees on “green” lessons learned.

“Sustainability” — maintaining a diverse bio-system while eliminating waste and pollution and decreasing energy consumption — is a hot topic in fashion, from Seventh Avenue to Europe. But it poses conundrums. Is it better for a Paris-based fashion company to use virgin paper produced in France for its runway show invitations? Or recycled paper from China? Can they just skip the fancy card stock and send evites?

Fashion schools are working a keener understanding of carbon footprints into their curriculums. There are green fashion contests challenging designers to make clothes that are both red-carpet glamourous and good for the planet. Countless brands now declare themselves eco-friendly, which can mean anything from using organic cotton in T-shirts to using solar power to heat their headquarters. Most are sportswear labels that lead with their self-declared “green” credentials rather than aesthetics; or hardy activewear companies, such as Patagonia, which offer handbooks for repairing — instead of replacing — damaged clothes.

But on the whole, green fashion is typically seen as “other.”

At the top of the fashion pyramid sit the luxury brands. In grand corporate offices, their executives speak of carbon credits, “cradle-to-cradle” supply chains and the exigency of preserving natural capital — the extravagant raw materials such as unmarred leather hides and long-fiber cotton on which their products rely.

These companies have natural eco-advantages over their mass-market rivals. They control more of their supply chain, such as tanneries. They have the resources to develop new production techniques. They tout the heirloom nature of their products, not their disposability. And their customers are less price-sensitive: Who’s counting pennies when spending thousands of dollars on a handbag?

“I honestly think the brands are doing what they’re doing because they think it’s good business” — a way to preserve the quality of the natural resources they rely upon, says Gemma Cranston, of the Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership, which has worked with Kering and Hugo Boss. “They just see it as a step they now need to take to continue to produce high-quality garments.”

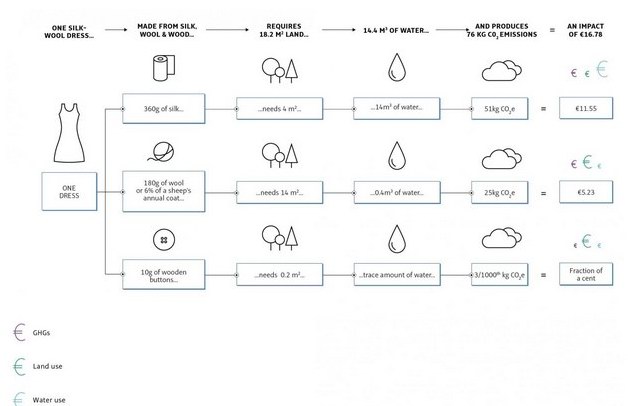

Kering has started quantifying the environmental impact of its products. This chart estimates the amount of land and water used and the amount of carbon emissions required to produce the silk, wool and wood for one designer dress, and assigns a Euro value for each factor. (Kering/Courtesy of Kering from its 2014 Environmental Profit and Loss Report)

The Paris-based LVMH, which controls Louis Vuitton, Céline, Givenchy, Christian Dior and Fendi, among other luxury brands, began to focus on sustainable business practices in 1992 in its wine and spirits division. This fall, LVMH announced the creation of a carbon fund that each brand pays into based on its energy consumption. The approximately $5.3 million fund supports projects such as upgrades from traditional lighting to LED.

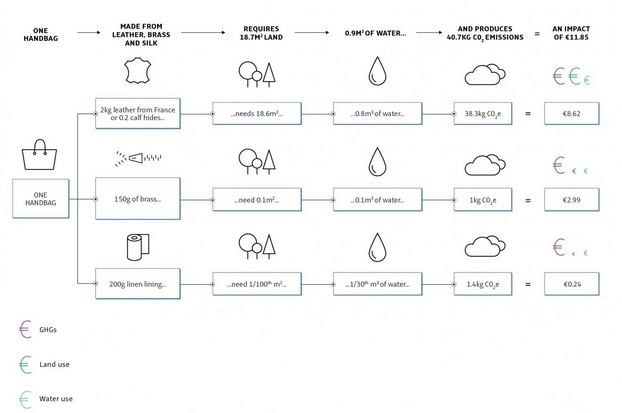

In June, Kering released its first Environmental Profit and Loss Report, examining where in its chain of more than 1,000 suppliers in 126 countries lurk the largest and gravest impacts on the environment. Looking at all its labels — from the silk T-shirts and motorcycle jackets of Saint Laurent to the sports gear of Puma — Kering measured water consumption, air pollution, greenhouse gas emissions and land use. It then translated these findings into euros to estimate how much the production of, say, a single leather handbag costs the environment: 11.85 euros last year, or about $12.53.

In 2013, Kering’s luxury goods cost the environment about $817 million. (A similar conglomerate, operating without environmental restraint, would have put a strain of $1.2 billion on the planet, according to PricewaterhouseCoopers.) In 2014, that environmental cost ticked upwards by 2.2 percent to $838 million — while revenue grew by 4.5 percent.

In this chart, Kering estimates the land and water usage and carbon emissions associated with producing the leather, brass and linen for one handbag. (Kering/Courtesy Kering, from the 2014 Environmental Profit and Loss Report)

Kering posted this data online so other manufacturers could learn from their lessons. “When you are speaking about sustainability, if you keep it all for you, you won’t change the paradigm,” says Marie-Claire Daveu, Kering’s chief sustainability officer.

The Kering report also revealed that only seven percent of the company’s environmental impact was at its boutiques, headquarters and warehouses. Fifty percent came from the production of raw materials. And 25 percent was from processing those materials. The most significant impact included the greenhouse gases from cattle ranching and the land and water dedicated to traditional sheep farming.

The goal is not to ban wool or leather but to find more environment-friendly ways to produce it. Kering and LVMH, for example, are moving away from traditional tanning methods that use chromium.

But bright candy colors typically cannot be produced without using heavy metals, says Sylvie Bénard, corporate environment director at LVMH. There’s also a concern with color stability. A customer can’t get caught in a rainstorm and find her handbag dripping dye onto her cashmere trousers. Gucci developed an organic tanning technique and in 2013, began using it to produce special-order, bamboo-handled bags. Louis Vuitton’s Gaia Monogram Cerise handbags now use vegetable-tanned leather.

The Gaia handbag from Louis Vuitton — an example of handbags that are “green” or a part of "sustainable fashion.” (Louis Vuitton)

Yet for all the openness expressed at the corporate level — Kering even tied executive bonuses to meeting sustainability goals — fashion is still fashion. It’s driven by desire, not environmental awareness or even logic.

Almost none of these brands weave sustainability into the mysterious magic of luxury fashion. Stella McCartney, known for her no-leather stance, is a rare exception. Her eponymous brand, part of Kering, sells fashion wrapped in an environmental sensitivity detailed throughout the company’s marketing.

More common is the situation at Saint Laurent. Corporate executives herald the use of energy-efficient LED lights in its boutiques. Yet when designer Hedi Slimane presented his Saint Laurent collection in Paris in October, he installed a dynamic light display — flashing with a near-blinding intensity — at the top of the runway.

Did he use LED lights, too? And were those lights reused after the show, which lasted barely 15 minutes?

“They are very secret about their fashion shows and would not like to answer any questions,” explains Marie-Laure Vaganay, a corporate spokeswoman.

And after Gucci invested years of research into developing a non-toxic leather tanning process, will examples of that leather be available to customers in its newest store? The answer is murky: Maybe. No. Probably not.

The story of sustainability is not trickling down to the product level, says Robert Burke, founder of the New York retail consultancy that bears his name. “Consumers look at luxury brands for exclusivity, quality and status. I’m not sure where sustainability fits in that pecking order.”

Consumers have been more vocal about labor practices and fair compensation, galvanized by scandals such as the fatal 2013 Rana Plaza factory collapse in Bangladesh. Yet, shoppers still gravitate to impossible bargains. It’s even harder to imagine them getting worked up about contaminated groundwater.

In the calculation to spend $5,490 for a washed-leather Saint Laurent motorcycle jacket, environmental awareness is not a selling point. And luxury brands are not attempting to make it one.

Daveu quotes her boss, Kering chief executive François-Henri Pinault: “We don’t do sustainability to please the customer and sell more bags. We do this because we have no other option. It’s a business and leadership opportunity.”

But if you’re going to sell bags anyway, wouldn’t promoting your more environmentally-sound bags be both good business and good leadership?

The prevailing image of “green” fashion — with its connotations of nubby fabrics and crunchy-granola styling — muddies the carefully crafted message of luxury fashion. Luxury consumers are drawn by romantic visions of skilled artisans at work over handmade oxfords. They are wooed by the irresistible notion of cool.

Is green fashion cool? Or simply good for you? Listening to someone brag about a new eco-friendly sweater is about as thrilling as a conversation about air filters. The Internet isn’t melting down from a run on sustainable textiles the way it is from the frenzy over shiny Balmain shirts.

But perhaps it could.

High-minded chefs pushed sustainability into the lexicon of every farm-to-table foodie. Toyota made hybrids cool. Tesla made electric cars glamourous.

“The role of luxury brands is to start a conversation and to create desire,” says Kwesi Blair, senior vice president of new business at Robert Burke Associates. “The biggest challenge? How do they want to make this topic — which hasn’t been sexy — sexy?”

Wooing customers with the sustainability of a Gucci or Louis Vuitton handbag might be a start.